Playing Flappy Bird with SPO

| GitHub Repo 👾 | Scope: ⭐⭐⭐ |

In 2013, the game to play was Flappy Bird. Flappy Bird is an infinite scroller with a simple premise and notoriously difficult gameplay. You must flap your wings to navigate the bird through approaching pairs of pipes, with your score being the number of pipes you make it through before dying. You get a bronze medal if your score was greater than 10, a silver for greater than 20, gold for 30, and platinum for 40.

Flappy Bird Medals

Due to it’s simplicity and popularity, many people have made Flappy Bird playing programs. You can find hand-coded, genetic, and Q-learning bots on GitHub. When I was learning reinforcement learning, I was drawn to policy optimization (PO). There was something I found very appealing about the entire brain being a neural network, so I decided my bot would play Flappy Bird via PO.

However, I was disappointed to find that almost everyone who wrote a learning bot didn’t learn on the original game. You see, at the height of its popularity, Flappy Bird was actually removed from the app store. Only after six months did the game reappear on the app store, but with a different look and feel from the original. Therefore, almost all bot authors decided to learn on either the newer version of the game or an imperfect clone. As Flappy Bird is a game with a very specific feel, playing these copies wasn’t nearly as fun to me. As a fan of the “classic” version, I thought I could carve out my niche by learning on the original game. But where would I get the code? I thought the original game was lost…

That was until I stumbled across the website flappybird.gg. It took about five seconds for me to realize that this is a true replication of the game. It feels just like the original. And with the JavaScript game logic sent to the browser not being obfuscated, I decided this would be the environment to learn with.

Initial Work

The website game was implemented using the PlayCanvas Engine, so after reading through the docs and familiarizing myself with the game’s source code, I began my work.

State Information

Certain entities hold critical position information for the network. Though the game appears to be the bird moving toward stationary pipes, interally the bird’s horizontal coordinate (the x coordinate) is fixed, and the pipes move toward the bird. Therefore, the (possibly) relevant information to learn from is

- The bird’s

ycoordinatebird.y - The bird’s (vertical) velocity

bird.velocity - The previous pipe’s

ycoordinateprevious_pipe_height - The closest upcoming pipe’s

ycoordinatenext_pipe_height - The next closest upcoming pipe’s

ycoordinatenext_next_pipe_height - The

xcoordinate of the pipespipes.x

Various combinations of these input streams are considered for my experiments. However, before experiments began, I needed to determine which ranges these values take on. As neural networks tend to prefer input values in similar ranges (usually between -1 and 1), I needed to guarantee that none of these values were significantly larger than the others. The facts I collected while examining the source and console output are:

bird.y > -0.65and is unbounded from above. The bird goes off the screen atbird.y = 1.bird.velocityin free fall is about4, so I scale the velocity by0.25.- For most of the game,

0.375 > pipes.x > -0.375, where the smallest value is closest to the next pipe. However, the game begins with a “tutorial” section that gives the player more time to figure out how the game works before attempting to pass through a pipe. Consequently, at game initialization we start atpipes.x = 1.64. - For all but the first three pipes,

-0.375 < next_pipe_height < 0.375. The first three pipes (internally) can actually range from-0.3to0.5, but as the first pipe initialized internally is not rendered as part of this tutorial, this only really affects the first two “experienced” pipes.

The strange initialization logic also means that the location of pipe1 is not always the closest upcoming pipe (ie. pipe1.y != next_pipe_height). Instead, it is only the next pipe in the tutorial section, and otherwise the next pipe is pipe2. The tutorial section is easily identified just by checking if the score is 0, which leads to this code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

if (this.birdScore === 0){

previous_pipe = 0.5;

next_pipe_height = pipe1.y;

next_next_pipe_height = pipe2.y;

}

else {

previous_pipe = pipe1.y;

next_pipe_height = pipe2.y;

next_next_pipe_height = pipe3.y;

}

This tutorial section also causes a more subtle issue. As the pipes.x variable can equal 0.375 in the tutorial section, the network would be given information at this location where it both was and was not currently inside a pipe at pipes.x = 0.375. This causes issues for the network, as there are datapoints in each trajectory at this x value that “get away” with flapping at this location, and others where they receive a game over.

To solve this, I defined a 0/1 indicator called isPastOne as part of the relevant information for whether the network was in this tutorial phase or not. This is a sudden value change for the network, but in practice the network learns to handle it well.

Reward Function

To define the reward, I stuck with the standard reward scheme for Flappy Bird agents, namely:

+0.01for every decision frame+1.00for getting a point-0.50for going above the screen (useful at the beginning of training)-5.00for dying0.99for discounting

The Optimal Return

As Flappy Bird is such a simple environment, we can compute the optimal agent’s expected return. A (slightly simplified) Flappy Bird trajectory looks like a sequence of small frame rewards $r_f$, with a large point reward $r_p$ every $a$ frames (for passing through a pipe). The sequence $(r_0, \dots, r_{n-1})$ ends with a death reward $r_d$. An example sequence of length $n$ with $r_f = 0.01, a=5, r_p = 1, r_d = -5$ has a reward stream of:

\[0.01, 0.01, 0.01, 0.01, 1.01, 0.01, \dots, 0.01, -5.00\]With discounting, the reward stream looks like:

\[0.01, 0.01 \gamma, 0.01 \gamma^2, 0.01 \gamma^3, 1.01 \gamma^4, 0.01 \gamma^5, \dots, 0.01 \gamma^{n-2}, -4.99\gamma^{n-1}\]Therefore, the expected return at time $0$ is

\[r_d \gamma^n + \sum_{k=0}^{n} r_f \gamma^{k} + \sum_{k=0}^{n} r_p \gamma^{ak}.\]As training progresses, the agent learns to survive longer, so $n$ increases. Sending $n \to \infty$ gives the optimal agent’s expected reward:

\[\lim_{n \to \infty}(r_d \gamma^n + \sum_{k=0}^n r_f \gamma^{k} + \sum_{k=0}^n r_p \gamma^{ak}) = \frac{r_f}{1-\gamma} + \frac{r_p}{1-\gamma^a}.\]For our example values above, this equals about $21.4$. This value is useful during experiments to know where convergence, at best, must occur. It’s really rare one can calculate this value symbolically, which is a byproduct of Flabby Bird’s simplicity.

Modeling

Next I needed to pick a learning method. I had already decided I wanted a policy optimization method, but which one? I decided to start small with the simplest PO technique, policy gradient.

Policy Gradient

The (vanilla) policy gradient (VPG) method essentially fits a state, action pair by computing the cross entropy gradients and scales each datapoint gradient with the “rewards-to-go”. This leads to stronger associations being made between states and actions that result in larger rewards-to-go.

I implemented a custom policy gradient network using tensorflow.js after reading OpenAI’s Spinning Up on DeepRL post for help. This was my first project with both tensorflow and JavaScript, so it took a little while to get comfortable!

I didn’t record my experiments as thoroughly as I did with future modeling efforts, namely because… policy gradient doesn’t really work. I probably performed 20 seperate multiple-hour experiments, culminating in a high score of 3. As I have read in many papers, VPG is very brittle. Issues range from breaking from slight changes in hyper parameters to failing to learn at all. I tried a flat baseline to subtract from the return, and couldn’t get anything to work. This is likely a failing on my end, but I did know that this environment was challenging to do with policy optimization, namely because of the cost of sampling.

The Cost of Sampling

I especially had trouble isolating VPG’s shortcomings with what I see as the critical challenge of Flappy Bird, the cost of sampling. What I mean by the cost of sampling is that when policy optimization samples actions based on it’s learned confidence in each move, sampling the less-confident move can instantly result in a game over. Said simply, in Flappy Bird it is hard to recover from a mistake. This means that this exploration is very likely to result in a game over. For example, even if the network is 99.0% sure of each of its moves for 50 decision frames (~7.5 seconds at snapshots every 0.15 seconds), the chance it makes at least one move that it is less confident in is

or 39%. This issue has an interesting affect on training. The network is required to have extremely high confidence to counteract the exploration sampling to reach a high score when sampling. This drastically slows the agent’s best attainable score when training. The positive aspect of this environment is that bad actions are “punished immediately”, so credit assignment is simple for the network. Therefore, I expected that during training, learning would be fast but plateau far below the optimal agent’s expected return, as the laws of probability fought against a highly-confident agent.

I decided that this was important enough of an issue for tracking performance that I occasionally had the agent play a game by selecting actions not by sampling but by argmaxxing. I made these “inference trajectories” relatively infrequent (1 out of every 20 training games). This, at the very least, gives me a better signal of progress than tracking average reward. That being said, I also include these inference trajectories into the training data. I am unaware if these “inference trajectories” are commonly trained on (or theoretically justified), but I did find them helpful in practice for logging.

Regardless, I was pretty disappointed that all this work with VPG didn’t lead to anything, but I knew there was better options. I decided to use the policy optimization algorithm that everyone uses: PPO.

PPO

For Proximal Policy Optimization, or PPO, I used an existing tensorflow.js implementation from this repo. PPO for the original Flappy Bird has been done before (shown on the YouTube channel ProgrammerTips), so I did have a reference for performance (though no hyperparameters). I conducted 9 experiments for PPO, which typically ran between two and four hours on my Mac, training in real time. In the next section I give the first set of hyperparameters I chose.

Experiment 1. Hyperparams

For my initial experiment, I set the actionFramerate=200, meaning that every 0.2 seconds the state is recorded and an action is taken.

The state array was bird.y, pipes.x, next_pipe_height. The actor network has a vanilla feed forward with dims 3,8,8,8,2. The critic shared the same architecture, except it ended in a single neuron for value estimation.

The network training hyperparams stayed constant, namely 10 epochs of full-batch training, weighting the critics’ contribution (often called $\lambda$) as 0.95. I used the elu activation function throughout, and an L2 regularization with a weight of 0.01.

After completion, Experiment 1 achieved a high score of 15.

Results

Over the course of the 9 experiments, I tried various combinations of the relevant state information, network and training hyperparameters. The highest score I achieved (during an inference trajectory!) was 41. I was happy to have a bot that could get a platinum medal, but the model was so inconsistent. Averaging over the scores obtained from running the model with argmax inference gave a measely 2.5. I needed a more consistent network! I’m sure I could have achieved this with PPO, but I wanted my project to have a bit of novelty to it. I decided to pick up a newcomer to the policy optimization scene: SPO.

SPO

While doing this project, I read the recently released Simple Policy Optimization paper. I got really excited, because it seems like this was just a free performance improvement. I modified zemlyansky’s PPO implementation to train on the SPO loss, and ran three other experiments. I got comparable results to my PPO experiments, where best performance was ok but the average was terrible.

I didn’t understand what was going on until I decided to consult a language model. I don’t usually like to use LLM output for personal projects, but I was pretty stuck after all these experiments. Gemini 2.5 Pro approved of my implementation, but hated my hyperparameters. Taking its advice, I

- removed a layer from each network

- decreased the action framerate to

50(20 network inferences a sec) - decreased the

numGamesperiterationto20(train from the data obtained from20 games) - decreased the

deathrewardto-1.5 - changed state array to:

1

2

3

4

5

6

state_array = [

this.velocity/this.velocity_scale,

bird_y - next_pipe_height,

pipes.x,

isPastOne

];

I ran a final experiment with these settings, which achieved the best results.

Experiment 4.

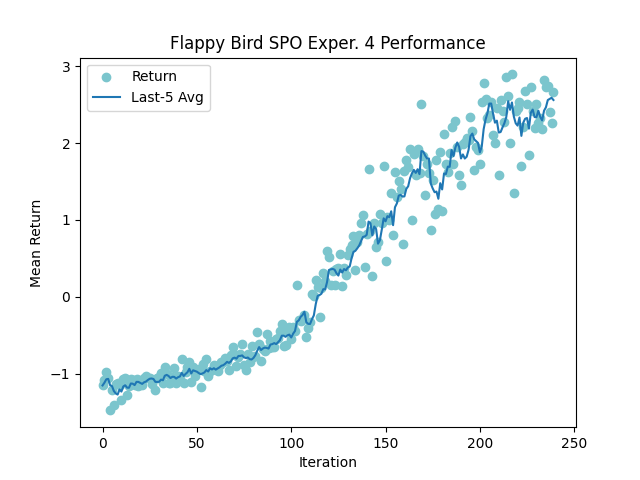

This experiment turned out very well. Plotting the mean return over each iteration (ignoring the initial 35 iterations where it learns to not flap off the screen) is shown below.

Such a consistent increase! This was a great sign for my consistency metric. After running 100 games of inference, I achieved a best score of 52, and a mean score of 10.0! My network officially averages a bronze medal. Here is the final visualization I made along with my cute little bongocat UI.

Conclusions

I now understand why everyone loves deepRL as much as they say it doesn’t work. I’m surprised by how challenging even a simple real-time video game is for the current state-of-the-art algorithms. I also learned a ton, including how modern PO algorithms work, the proper hyperparameters for a simple environment, and the basics of Javascript and tensorflow.js. Watching the cat finally learn to play this game well was incredibly rewarding.

As a final note, to get in the 2013 mood I listened to the hit songs from the time while developing. Feel This Moment by Pitbull and Christina Aguilera is such a great song.

Resources Used

- I built the environment from the sourcecode from flappybird.gg

- I customized the repo of the tensorflow.js PPO implementation by zemlyansky

- I customized the loss function following the Simple Policy Optimization paper

- I customized the bongocat assets from this repo

- I used Plotly to make the weights heatmap (viridis of course)

- I edited the game’s spritesheet using Piskel to make this post’s cover image